It’s not often that one has the patience (or even the desire) to read an enormous book. In terms of time and energy, committing to a 500–1,000-page volume is not unlike applying yourself to a serious relationship. You do not simply read a book this long — you live in it for a while.

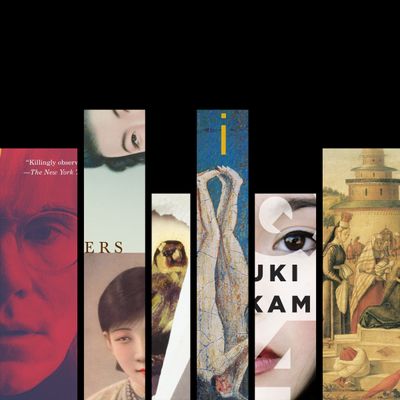

Which is precisely why, after being told that many of us would be homebound for the foreseeable future, a gigantic brick of a book feels like just the ticket. (For some, staying at home has not been conducive to reading; if that’s you, please see our short-story roundup.) But for those of you who are craving some girth, you’ve come to the right place; below, a roundup of the very best, big, 500+-page books, courtesy of the Cut staff.

New! You can now save this product for later.

There are books you read and then books you inhale, and for me, Holy Terror was the latter. The holy terror of the title is Andy Warhol, who reshaped not only 20th-century art but just about the entirety of 20th-century culture (and a fair chunk of the 21st) in his silk-screened image. The book is written through the eyes of Bob Colacello, who from 1970 through the early 1980s was Warhol’s acolyte, consigliere, and editor of his Interview magazine. Colacello is a meticulous diarist (not unlike his boss, whose diaries are also required reading, as comprehensive an encyclopedia of American misbehavior as exists) and a shrewd observer of the work, the parties, the lunacy, and the tradecraft of the business of art and culture in the ’70s. And though Warhol has been biographized time and again, this portrait — a small chunk of his insanely productive life — feels fuller-fleshed and more knowing than any other I’ve ever read. Some writers give short shrift to their subjects, from envy or rivalry or God knows what. Colacello, to his credit, lets his memoir loll. It is nearly 700 pages long. I would have read 700 more. — Matthew Schneier, Features Writer

New! You can now save this product for later.

I gave up on Murakami’s 900-page brick of a dystopian novel last February because it was cold and dark out and this isn’t a warm hug of a story; rather, it’s like a mushroom trip that runs uncomfortably long. In spite of that (perhaps because of it), it only took me a few pages to get sucked back into Murakami’s uncanny Tokyo. It’s one that’s ostensibly the same as the real Tokyo, except two moons hang in the sky, and a mysterious evil, dubbed the Little People, are spiriting away young girls in chrysalises they spin from the air. Our main character is a professional assassin, Aomame, whose discipline recalls a childhood spent in a religious cult (religious cults are the other diabolical force in 1Q84). Employing his particular brand of magical realism, Murakami’s characters must contend with the harshest problems of the real world — domestic violence, rape, lonlieness, love, and grief — all while questioning their reality, which in 1Q84 is horrifyingly tenuous. — Sangeeta Singh-Kurtz, Senior Writer

New! You can now save this product for later.

Mating is my favorite book not just because it’s perfect but because it really should have been a failure. The novel — Rush’s first, and written in his 50s — is narrated by a nameless white American woman doing research in Botswana when she falls in love with a charismatic American expat who’s created a secretive utopian community deep in the Kalahari desert. And yet it’s a convincing, tragic glimpse at what it takes to change entrenched systems of patriarchy and imperialism. Though the book makes plenty of detours into international-development theory and employs a truly overachieving vocabulary, its plot is relentless. I’ve recommended it to more people than I can count. — Jordan Larson, Essays Editor

New! You can now save this product for later.

This definitely qualifies as one of those longer books I’ve vaguely wanted to read for a long time but never got around to until I was trapped in an apartment with my boyfriend’s roommate’s makeshift library and had the pick of the lot. Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s novel of four well-to-do Osaka sisters is an immensely satisfying epic of disappointment in marriage, nationhood, and gastrointestinal health. It is equal parts a novel about Japanese society in the years leading up to and through the beginning of World War II and a paean to the wonders of vitamin B injections. I found it a perfect book to read just now: Its charms are domestic but hardly confined. Every hundred pages or so, a bad storm will brew, and as the years pass, the exhibition of spring’s blossoms never fails to delight. — Hannah Gold, Writer

New! You can now save this product for later.

For the past year, George Eliot’s Middlemarch, a verified classic that supposedly paints a rich portrait of 19th-century provincial life in a fictitious English town, has been at the top of my list of books to read. However, I’ve long been putting it off, seeing as it clocks in at almost 900 pages. But I’ve now lost my most compelling excuse for not reading it: I used to tell myself, it’d be extremely difficult to hold up this book with one hand while squished on a packed subway car. Seeing as I’m now exclusively reading in bed, its time has come. — Amanda Arnold, Writer

New! You can now save this product for later.

I have been reading The Gulag Archipelago since … January. I have literally been reading this book all year, and I’m still only on Volume 1. I’m not going to lie — this is a really hard book to get through. It’s long, dense, and a quarter of the time, I barely understand what I’m reading, but it’s also a really beautiful book, and it’s full of hauntingly relevant lessons from the past we definitely should have learned by now (i.e., if you don’t punish evil behavior, it will “rise up a thousandfold in the future”). So much of what Solzhenitsyn has to say about the Russian gulags still feels relevant to what is happening in America today, so much of the heart and soul of this book feels like it’s about all the things we should have learned that we somehow haven’t yet. “It is unthinkable in the twentieth century to fail to distinguish between what constitutes an abominable atrocity that must be prosecuted and what constitutes that ‘past’ which ‘ought not to be stirred up,’” Solzhenitsyn writes. “We have to condemn publicly the very idea that some people have the right to repress others” — Aude White, Senior Communications Manager

New! You can now save this product for later.

If there’s ever been a time for you to finally pick up Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, a whopping almost-800-page book that also is wildly divisive, it’s now. As the president of the pro-Goldfinch fan club, I highly recommend reading the wild story of Theo Decker, who survives a bombing at a New York museum, while his mother doesn’t. Orphaned and forced to live under the watch of his deadbeat dad in Las Vegas, Theo becomes anchored by a painting that has come into his possession which inadvertently becomes a focal point of his life. The Goldfinch is a sweeping novel that shows how tragedy and grief can mold us into who we become and how art can save us. I’ve read it at least three times and have the last three pages of the book saved on my phone, so if that’s not a glowing recommendation, I don’t know what is. — Kerensa Cadenas, Senior Editor

New! You can now save this product for later.

I read this in high school, with a teenager’s boundless enthusiasm for staying up all night reading engrossing novels. I don’t know if I’d still fly through it today. It’s set in the 11th century and follows the main character’s journey to study and master medicine. That sounds lame, but there’s a reason I don’t work in advertising. It’s very good. — Rachel Bashein, Managing Editor

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.